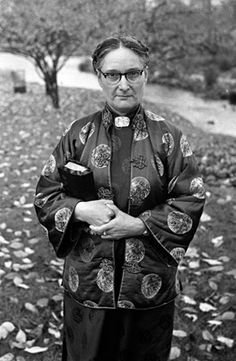

Gladys Aylward

Gladys had been a parlor maid, having left school at sixteen, and was used to doing menial jobs such as scrubbing door steps in middle-class London homes. But there was fire in her bones and at age 27 she felt the strong call of God to go as a missionary to China. With no training as a nurse or teacher there was no chance that established missionary societies would accept her for training so she slowly and quietly put aside all her saving until she was able to get the required 47 pounds, 10 shillings for a one way train ticket to Tientsin, China. This was the cheapest fare possible but it meant going via the Trans Siberian Railroad.

She set out a month after I was born and arrived at the mission station at Yangcheng, Shansi, China a month later. She had almost been forced to stay in Russia to “help with the revolution” when the authorities changed the profession on her passport from Missionary to Machinist.

There have been at least three books written about Gladys and Ingrid Bergman starred in a popular movie about her called “The Inn of the Sixth Happiness”. I was only two when she came to stay with our family at Linfen for a few weeks, to help in my Daddy’s hospital. She looked after us three children when our mother had to go to Peking for an operation. I feel honored that she cared for us and gather that we were relatively well behaved. Those were her early days when she was still learning the language. Twenty years later she visited our home south of London and we laughed about it together.

Once settled in China, she became so identified with the people that she eventually put aside her British citizenship and became Chinese. This was a huge and somewhat dangerous step in the precarious 1930s, as she would no longer be under the protection of the British government. Not that the British were able to give much protection to missionaries out in the interior.

Before the violence that erupted in Shansi province in 1937, with the three cornered war between the Japanese, the Nationalists and “the Reds” as Mao’s forces were called, Gladys was hired by the mandarin of the city of Yangcheng to be chief “Unbinder of womens’ feet”. Until the overthrow of the Ch’ing Dynasty in 1912, it was considered fashionable and a sign of upper class breeding for Chinese women to have small feet. So, from an early age, diligent mothers would tightly bind their daughters’ feet. Can you imagine the growing pains! All that changed with the Republic but the change was slow in distant provinces such as Shansi. Gladys had the challenging task of visiting homes in and out of the city, chatting in the local dialect and, after a generally friendly introduction, would ask to be shown all the feet of the women and girls in the household. This suited her personality perfectly and it was the happiest period of her life. It became a metaphor for the spiritual unbinding of bondaged lives through the Christian Gospel.

Later, with the Japanese advancing from the east, she showed incredible courage by taking over a hundred children across two mountain ranges and the Yellow River to Sian, a distance of 130 miles. They all arrived safely but she broke down physically and mentally with the strain and took months to recover.