My New Memoir - Persistence of Light

in a Japanese Prison Camp, over the Alps with an elephant and then in Silicon Valley, published August 2018.

It is set to Newton's seven colors of the rainbow:

Parachutes over Weihsien Camp

Chapter 1: Red.

A Childhood in China, up to age 13.

Chapter 2: Orange.

Postwar Britain. High School and Army

Chapter 3:Yellow.

Cambridge - Exploring Hannibal's tracks.

Chapter 4: Green.

An Alpine Journey - with Jumbo

Chapter 5: Blue.

Silicon Valley and the Counterculture

Chapter 6:

Love, Marriage and a Growing Family

Epilogue: Violet.

Poetry, Art and a New Life

Highlights include:

Life in China in the 1930s in a large medical missionary family of four boys and two girls.

Terrorist atack

Life as an orphaned boy in a Japanese Internment Camp

Seven parachutists setting the camp free.

The Cambridge Hannibal Expedition in search of Hannibal's route over the Alps.

The British Alpine Hannibal Expedition, following Hannibal over the Alps with Jumbo, the elephant.

Coming to the US. Appearing on the television program "To Tell The Truth".

The birth of Silicon Valley and the new Counterculture.

founding Spectrex Corp.

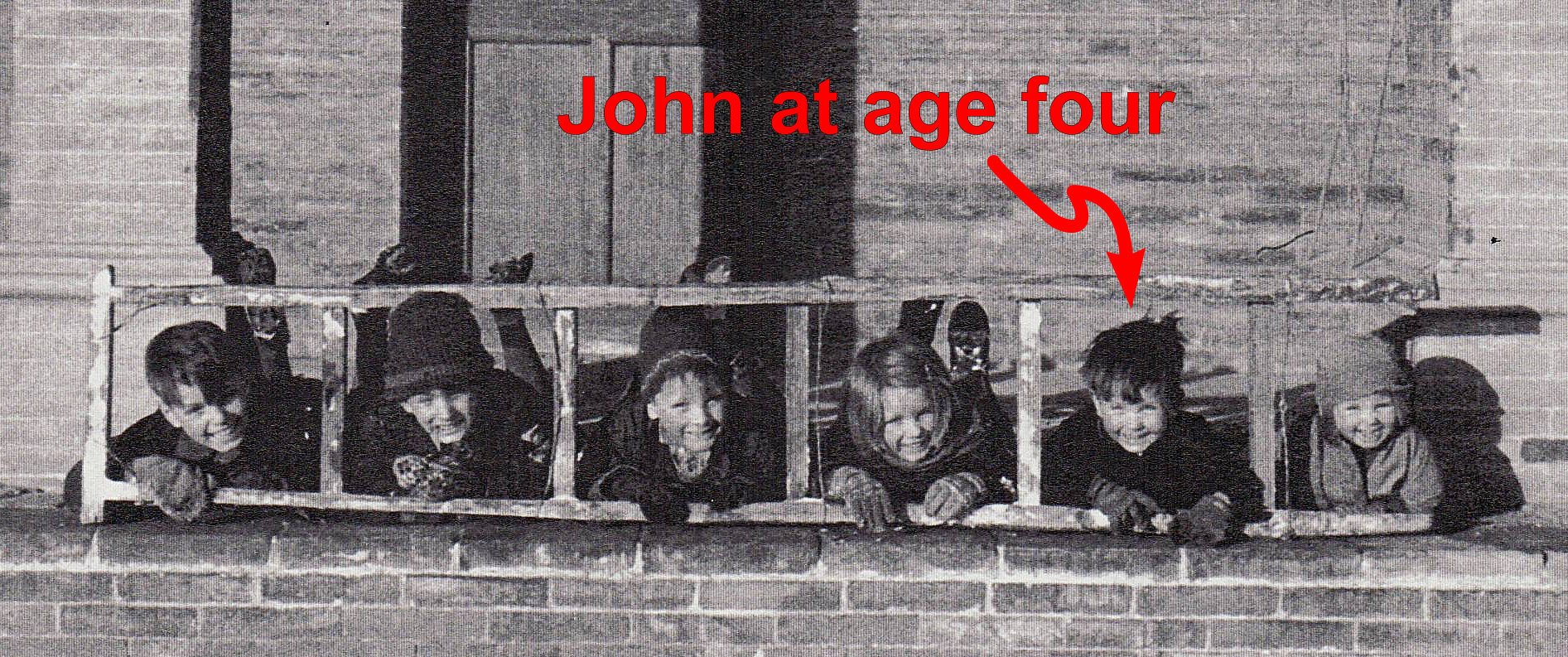

The Hoyte kids: Robert (Robin), Eric, Rupert, Mary, John and Elizabeth ... in Ping Yang Fu, China

Our team on the Hannibal expedition.1959. From left: Baldi, Michael, Richard, John, Ernesto and Colonel John Hickman. Cynthia and Claire on truck, Jimmy on Jumbo.

My dad, Dr. Stanley Hoyte, married my mom, Grace Wilder, in Peking 1922

Early memories. Creating patterns of light.

SAMPLE CHAPTERS FROM THE MEMOIR

Chapter 1 – The Terrorists Attack. China 1934

I was just two-and-one-half years old when our town, Linfen, was besieged by communist forces. They were acting more like a militarized gang of terrorists, thugs or bandits, than a regular army with central control. They’d destroyed villages, killing the land owners and imprisoning the women and children until their husbands were able to come up with ransom money. A year earlier, the “Reds” had murdered two young American missionaries, John and Betty Stam. The Stam’s three-year-old baby, Helen, had been saved only because a Chinese Christian offered his life for hers. The same brutal section of the Red army had crossed the Yellow River and was pillaging our province and threatening to attack Linfen. At this time, my three brothers were safe at Chefoo but my parents had Mary, aged five, my baby sister, Elizabeth, aged one, and me at home with them. Some years later I discovered my mother’s diary about the danger we faced.

Was I afraid? I was not afraid of actually dying at their hands. But I was afraid for the children. I should have liked to protect them from being scared or hurt. And yet as I faced this fear I knew that if I set the right standard, they would be as brave as I wanted them to be. Children are heroes at heart, for all heroic stories appeal greatly to them. So I trusted God to give me courage and strength when the time came to show them how to be brave.

Then came another question. What if we were killed and the children left? I had a talk with good old Mrs. Tang, our children’s nurse, who said of course she would do her best for them in that case. Let me say here, what a help it is in such straits to face each question honestly and to talk it out with the person concerned. It is wonderful what strength God gives in our desperate situation.

Then came another question. What about our three boys at boarding school? We faced it together. It would seem terrible to deprive them of a mother’s and a father’s loving sympathy and continued care. It was a great relief to write to Robin a long letter, telling him of the facts and of what might happen to us, saying how brave we knew he and his brothers would have been if they were here and urging them to keep close to Jesus all their lives. I wonder if this letter ever reached him. Perhaps the Reds got it instead. Then we asked God to enlighten our minds to show us what we should do in order to ‘be prepared.’

. . . Stan is feeling responsible for all the hospital staff. He was able to find places of escape from the hospital. As I was walking in the garden with him, we wondered where we as a family could hide. He mentioned the dry well, but it looks so deep and dark that I shuddered. I should not like to be shut up in it with three small children. Our best plan was to create a secret place in the house. We bricked up a doorway which led into two old storerooms in the corner of the courtyard. The only way of reaching them would then be by scrambling onto the kitchen roof, over a small sloping roof, and across the great main roof which was large and sloped quite sharply, so much so that a terrorist might well hesitate to walk on it. At the other end a ladder would be standing, down which we could climb to the walled in courtyard, the only access to our secret. We furnished these two rooms with a bed, some mattresses, boxes for storing bedding and food, a stove and a chimney, a chair and stools, wash basin, pails, a candle and matches, and paper and pencils for the children. We also put in a store of coal, kindling and paper and a water butt, while a local bricklayer blocked off the entrance from the house. We are a bit anxious about this as he is a talkative old man. It is impossible to do anything secretly in this country. The brick- layer thinks that we want to put our treasures there and so we do, for our children are our treasures. Mary is perfectly sweet about it all. She is the only child who can understand. Having heard all about Peter Pan and the Pirates, it seems to her as if she were living in an exciting book. She skips along over the roof, climbs boldly down the ladder, and helps me put away all sorts of useful things. We practiced climbing over the roof with John, aged 2 1/2, and Elizabeth as a baby in our arms.

The trouble was that to get to the secret rooms we had to climb over a roof that was visible from the city gates so that there was the danger of being seen by the terrorists or townsfolk friendly towards them. The city was closely shut up for two weeks, and there must have been prevailing fear of mayhem. My father quietly prepared for the worst. I dimly remember the hidden room and the idea of keeping it secret but was totally unaware of the fact that I could have been orphaned or killed at any time.

A remarkable coincidence occurred that we only discovered many years later. My mother noted in her diary that my parents had received a telegram from their friend, a Miss Deck, who wrote: We go Kaifeng. Yuincheng evacuated. This turned out to be Phyllis Deck, the aunt of my wife, Luci. Phyllis was killed while trying to escape the terrorists. Amazingly, Linfen was never attacked, although enemy forces came within a mile of the gates.

Chapter 4 – An Alpine Journey with Jumbo

It was September 1958, a little over two years after our original Cambridge expedition, and none of us four had been thinking of doing anything more with the Hannibal story. The big write-up in the London Times had been more than we could have hoped for, and now there were just sweet memories. By this time I was a graduate apprentice at Joseph Lucas Inc., an auto and jet engine equipment manufacturer in Birmingham, England. A friend and I were both staying at the downtown YMCA. Joe was working at a start-up social welfare organization. He was interested in planning a climb in the Alps, so one evening I sat down with him, showed him the slides and the scrapbook of our trip. I had been about to go off to bed when he came out with the ridiculous question: “Why don’t you take an elephant?”

Was it flippant? Was it simply imaginative? Perhaps a challenge? I never asked him. Whatever the reason, the question stuck in my head even though, laughingly, I recounted all the reasons why it would be impossible: No money. No elephant. No experience. No reason to justify it. No possibility. No way! However I could not get to sleep that night and began to think outside the box and put aside the impossibilities. I let myself imagine the possibilities! Suppose I was actually able to get an elephant. What then? I quickly started to think in terms of we instead of I, for Richard, my best friend at Cambridge, would have to be involved if anything as far out as this were to work. We shared the same crazy imagination and had already climbed Hannibal’s possible passes together.

What kind of elephant should it be? Well, of course, it would certainly have to be Indian, as African ones were hard to tame and notoriously unreliable. A comforting thought interjected itself as I was reminded that the British Museum had shown us Carthaginian coins with both Indian and African elephants rampant. What about a team? How about equipment? We would need insurance. My mind shut down when I thought of the enormous costs involved, and it was probably at this point that I eventually got to sleep.

Next day was just another day at work, but the evening was free so I got out my little portable typewriter and put together three letters, each to a British consul. Their locations were Geneva, Switzerland; Lyon, France; and Turin, Italy—the closest major cities to the Col de Clapier. My request was simple: Would they happen to known anyone who might have an elephant available for a British expedition over the Alps following Hannibal’s route? Of course, I couldn’t write as a penniless engineering apprentice in the Midlands of England. So with nothing but sheer audacity to back it up, I wrote representing a new entity: The British Alpine Hannibal Expedition.

There was very little chance of anything in return beyond a courteous letter from one of Her Majesty’s Consul Generals. I did wonder what kind of responses might ensue, and if they would contain just a little whimsy and humor. If you ask a crazy question, you might get a crazy and interesting answer. I could not ask for anything more.

A week later, I was waiting in line for the buffet supper at the YMCA, in possession of a long envelope from Turin that I had just picked up from the mail room. The line was moving slowly, so there was time to open it, revealing the Royal Coat of Arms and the words “British Consulate, Turin,” as the letterhead.

Sir: Unusual as your request may be – well, unusual, I should perhaps say, for a Consulate – I am happy to inform you that I have been able to secure the offer of an elephant for your projected crossing of the Alps next summer. . . .

My eyes grew wider and wider as I read and reread the letter. It went on to say that on the very day that my letter arrived, La Stampa, the local newspaper, had mentioned a particularly energetic young elephant at the Turin Zoo. Thereupon Mr. Bateman, the Consul General, picked up his phone and called the Zoo, reaching Signor Arduino Terni, Managing Director. Bateman asked: “Would you have an elephant available for a British expedition over the Alps following Hannibal?” Sight unseen and quite incredibly, not only was the response positive, but Signor Terni offered to provide the elephant free of charge. No doubt he thought of this as a good publicity but the sheer act of generosity overwhelmed to me. Our generous Signor Terni had only two requests: that we have the elephant insured and that the crossing would be in the summer rather than in the fall when Hannibal would have been caught in the snow.

Imagining Jumbo, our elephant, striding along with our group as we ascended the Alps,, was still hard for me to consider, but there it was. I had an elephant for a new expedition and the greatest hurdle of all, finances, seemed magically to have disappeared. During the next day or two the reality of the offer began to sink in. But then along came the doubts.